Listen to " THE DREAMS " 7.1.4 | APPLE MUSIC

Listen to " THE DREAMS " | AMAZON MUSIC

Listen to " THE DREAMS " | TIDAL

Buy to ” THE DREAMS ” | ITUNES

Buy to ” THE DREAMS ” | AMAZON

LIsten to ” THE DREAMS ” 7. 1. 4 | APPLE MUSIC

Off the Beaten Track Through the Sound Gardens of Juraj Ďuriš

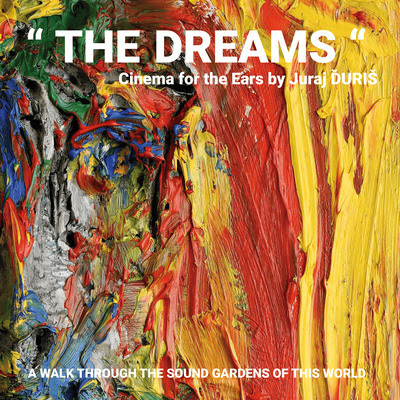

Juraj Ďuriš (born 1954) decided to include nine compositions, or “sound images” as he often refers to his works, on his portrait double album. The dramaturgical selection not only represents the development of his musical (or audiovisual) thinking, it also captures the poetic peculiarities of his style. It is thanks to these that the compilation, recording four decades of Ďuriš’s artful electronic “magic with sounds,” has the character of a monograph. The prefix “mono” in this case refers to one author, one intention, a unified whole, and a unique style. The author has accentuated this wholeness by linking his compositions into four sound continua, arranging them over the sides of the two gramoplates without separating pauses between the tracks. He invites listeners to “walk through gardens of images,” in the recesses of which he has planted aural associations. In doing so, he cleverly resolves the poetic and aesthetic differences between works from different periods; after all, for a garden to be impressive, it should be varied and at the same time coherent and stylish.

Wandering through the sound gardens of Juraj Ďuriš is a listening adventure. The author has shown himself to be a master of audiofiction and audio-mimesis; after all, he describes himself as a creator of sound images and combines his “other music” with cinematographic (“cinema for the ears”) and psychomagical (“hallucination”, “a form of magic”) ambitions. Whatever the case, Ďuriš’s “Imago Sonoris” represents a valuable and, above all, authentic contribution to the audio archive of modern Slovak music.

Jozef Cseres

Prague – Nové Zámky, July 2023

The short Imago Sonoris (2007) doesn’t open the album by accident. The melancholic ‘cello lament indexically suggests that the image in Ďuriš’s conception need not be exclusively iconic; correspondence through associative affinities is more natural to non-verbal sound design because the sonic material is not fixated on conventional verbal meanings. It can become an effective musical symbol due to the spontaneous activation of aesthetic-psychological mechanisms in the listener’s consciousness. The beats and reverberations in the opening of The Dreams (2023) foreshadow spatiotemporal movements across an imaginary landscape, rendered by percussive sonorities, in the resonant interstices of which the voice of John Cage can be heard, declaiming his lecture Composition in Retrospect with precision. Clearly articulated words and phrases float in a dreamlike environment defined by the psychoacoustic coordinates of the imaginative mind, as if willing to forgo settled meanings in favour of vague, phonic expression. Ďuriš’s Dreams is an invitation to a garden of “hermetalinguistic” sonic delights, where the grain of the assertive voice is pollinated by excited timbral vibrations. The listener is snapped out of a lethargic, dreamy mood by the familiar jingle of a time sign. It announces the entry into another soundscape, entitled Lost Memories (2015). A metronome begins inexorably to tick away the time of biological determinism, its transience attempting to be delayed by a final, sad cello melody. Not only gardens tend to be varied; times vary too. Physical time does not coincide with psychological time. The reversible time of a myth or dream has a different timekeeper than the irreversible time of human existence. The imaginative metro-rhythm of musical representation can work wonders with time. Peter Zákuťanský additionally animated Lost Memories with archival film images of ancient Bratislava, transformed beyond recognition by the destructive interventions of civilization. It was a lucky idea, because the audiovisual version of the work reveals Ďuriš’s audio-mimetic sense.

Panta Rhei (2007) is, of course, about flow. Along with time, space also “flows”. As the ‘cello unwinds time, the electronics modulate and multilaterally expand and contract space. The transversal interactions of time (melody) and space (dynamic blocks of sound) aestheticize the garden; indestructible time insistently insinuates itself into the listener’s consciousness, the deterritorialized melody eventually takes over the entire space, enveloping the garden in a sombre mood. Portrait (1989), Ďuriš’s joint audiovisual work with the artist Miloš Boďa, is primarily about transformations. The visual and sonic metamorphoses of phantom shapes between the figurative and the abstract (video) and the non-representational and the narrative (music) keep the viewer/listener in a constant psychological tension. The authors cinematically play with allusive associations, relying on the vagueness of the boundary between association and hallucination. They almost mischievously toy with our imagination with the sole aim of arousing in us an aesthetic pleasure based on the attraction of mysterious, indifferent meta-themes and meta-images. Compared to the original version of the work, presented in exhibitions within the genre category of video art, the newer, audio version is shorter by three and a half minutes. Relief after exiting the hallucinatory labyrinth is to be provided by a light surprise in the form of the heretical, mozartian Leck mich am Arsch, Jonicu! (2017). The ghost-filled enigma in the title refers to Amadeus’s misplaced pun, which Ďuriš has artfully wrapped in a trans-genre sound, in the spirit of the key thesis of postmodern aesthetics, “anything goes.”

Silhouettes (2017) returns the listener to the world of sound-space phantoms, where the silhouettes of possible entities are hinted at by simulating the playing of a five-stringed stringed instrument the “Milanolo,” a hybrid of violin and viola; it was made for violinist Milan Paľa in the Brno violin workshop Bursík. The silhouettes are a joint work of composers Ďuriš and Rudolf Pepucha, and virtuoso instrumentalist Paľa. The live Milanolo plots dynamic curves in a synthetic, sound-modulated space, after which only ephemeral silhouettes remain, presentimental traces of the real presence of hand-sounded silhouettes in space-time with virtual coordinates. Chronos I (1983), Ďuriš’s electroacoustic debut, is a garden par excellence. It is a tenacious sonic growth in vegetal development, where the dominant rhythmic motif is arborescent in nature, punctuated by rhizomic refrains which, given the straightforwardly self-referential representation of time, are not easily deterritorialized in the pulsating growth. Music and its primary medium, time, are here organically “congealed”, merging in the listener’s inability to determine the boundary between chronometric meter and freely pulsating rhythm.

Ephēmeros (2021) is the ex-ante soundtrack to Jakub Pišek’s video. Again, it is the opening melody from the first garden that opens the space, in this case an artifice of an out-of-time landscape. The melancholy thus remains, but the phantom distance takes (phantasmagoric) turns, both aurally and visually. The bewildered listener/viewer finds himself at the interface of two worlds, the ‘cello melody keeping him in the sensory one, the electronic soundscape telepresenting him into the unfathomable reaches of cosmic fiction. If only he’d known that the sci-fi setting was simulated in a bathroom, where the allusive “twist” in the washing machine drum suggests fabulations beyond the boundaries of ordinary imagination… The equally suggestive Dreams (1987) is entirely built on the association of spatial relations through the stereometric unfolding of sonic ‘surfaces.’ Alternating and parallel juxtapositions of reverberations and reverberations of abstract and ‘concrete’ sounds are used with the intention of evoking a dreamlike surreality. The rich, purposefully constructed sonorities of the early work reveal the directions Ďuriš’s sound creation will take in the years to come. Because the gardens are not arranged chronologically, but according to musical-aesthetic criteria, the listener repeatedly finds himself not only in virtual spaces, but also in temporal loops, to which the impressive ‘cello motif of “eternal return” contributes.

Scestné putovanie zvukovými záhradami Juraja Ďuriša

Juraj Ďuriš (nar. 1954) sa rozhodol zaradiť na svoj profilový dvojalbum deväť skladieb, resp. „zvukových obrazov“, ako svoje diela často označuje on sám. Dramaturgický výber nereprezentuje len vývoj autorovho hudobného (prípadne audiovizuálneho) myslenia, zachytáva tiež poetické zvláštnosti autorského štýlu. Práve vďaka nim má kompilácia, zaznamenávajúca štyri desaťročia Ďurišovho umného elektronického „čarovania so zvukmi“, monografický charakter. Predpona „mono“ odkazuje v tomto prípade na jedného autora, jeden zámer, jednoliaty celok i na jedinečný štýl. Autor prízvukoval túto celistvosť aj tým, že svoje kompozície prepojil do štyroch zvukových kontinuí, keď ich na všetkých stranách oboch gramoplatní zoradil bez oddeľujúcich páuz medzi jednotlivými trackmi. Poslucháčov pozval na „prechádzku záhradami obrazov“, v zákutiach ktorých im nastražil aurálne asociácie. Chytro tak vyriešil poetické a estetické odlišnosti medzi dielami z rôznych období; veď aby bola záhrada pôsobivá, mala by byť pestrá a zároveň koherentná a štýlová.

Putovanie zvukovými záhradami Juraja Ďuriša je posluchové dobrodružstvo. Autor sa v nich ukázal ako majster audiofikcie a audiomimézy, napokon, sám sa pasuje na tvorcu zvukových obrazov a svoju „inú hudbu“ spája s kinematografickými („kino pre uši“) a psychomagickými („halucinácia“, „forma mágie“) ambíciami. Akokoľvek, Ďurišov „Imago Sonoris“ predstavuje hodnotný a hlavne autentický príspevok pre audio archív modernej slovenskej hudby.

Jozef Cseres

Praha – Nové Zámky, júl 2023

Záhrada prvá

Kratučký Imago Sonoris (2007) neotvára album náhodou. Melancholický violončelový nápev indexovo naznačuje, že obraz v Ďurišovom ponímaní nemusí mať výlučne ikonický charakter; usúvzťažnenie prostredníctvom asociačných príbuzností je pre neslovesnú zvukotvorbu prirodzenejšie, pretože sónický materiál nie je fixovaný na konvenčné verbálne významy. Môže sa stať účinným hudobným symbolom vďaka spontánnej aktivácii esteticko-psychologických mechanizmov v poslucháčskom vedomí. Beaty a dozvuky v úvode kompozície The Dreams (2023) predznamenávajú časopriestorové pohyby naprieč imaginárnou krajinou, stvárnenou perkusnými sonoritami, v zvučiacich medzipriestoroch ktorých zaznieva hlas Johna Cagea, precítene deklamujúceho svoju prednášku Composition in Retrospect. Zreteľne artikulované slová a slovné spojenia sa vznášajú v snovom environmente, definovanom psychoakustickými súradnicami obrazotvornej mysle, akoby sa chceli vzdať ustálených významov v prospech vágneho fónického vyjadrenia. Ďurišove Sny sú pozvánkou do záhrady „hermetalingvistických“ sónických rozkoší, kde je zrno asertívneho hlasu opeľované vzrušenými timbrovými vibráciami. Z letargickej snovej nálady vytrhne poslucháča dôverne známa znelka časového znamenia. Ohlási vstup do inej zvukovej krajiny, autor ju nazval Lost Memories (2015). Metronóm začne neúprosne odbíjať čas biologického determinizmu, jeho pominuteľnosť sa snaží oddialiť záverečná smutná violončelová melódia. Nielen záhrady bývajú pestré, rôznia sa aj časy; fyzikálny sa nekryje s časom psychologickým, reverzibilný čas mýtu či sna má inú časomieru než ireverzibilný čas ľudskej existencie, nápaditá metro-rytmika hudobnej reprezentácie dokáže robiť s časom zázraky. Peter Zákuťanský dodatočne animoval Stratené spomienky archívnymi filmovými obrazmi starobylej Bratislavy, transformovanej na nepoznanie deštrukčnými civilizačnými zásahmi. Bol to šťastný nápad, pretože audiovizuálna verzia diela vyjavila Ďurišov audiomimetický zmysel.

Záhrada druhá

Panta Rhei (2007) je samozrejme o plynutí. Spolu s časom „plynie“ aj priestor. Violončelo odvíja čas, elektronika moduluje a multilaterálne rozpína a zmršťuje priestor. Transverzálne interakcie času (melódie) a priestoru (dynamických zvukových blokov) estetizujú záhradu; nezničiteľný čas sa neodbytne vrýva do vedomia poslucháča, deteritorializovaná melódia nakoniec ovládne celý priestor a zahalí záhradu do pochmúrnej nálady. Portrét (1989), Ďurišov spoločný audiovizuálny kus s výtvarníkom Milošom Boďom, je predovšetkým o premenách. Vizuálne a zvukové metamorfózy fantómových tvarov na pomedzí figurálneho a abstraktného (video) a nereprezentatívneho a naratívneho (hudba) udržiavajú diváka/poslucháča v neustálom psychologickom napätí. Autori sa kinematograficky pohrávajú s aluzívnymi asociáciami, spoliehajúc sa na vágnosť hranice medzi asociáciou a halucináciou. Až zlomyseľne sa pohrávajú s našou predstavivosťou s jediným cieľom – vzbudiť v nás estetickú rozkoš, založenú na príťažlivosti tajomných indiferentných metatvarov a metaobrazov. Oproti pôvodnej verzii diela, prezentovanej na výstavách v žánrovej kategórii video umenie, je novšia audio verzia kratšia o tri a pol minúty. Úľavu po východe z halucinačného labyrintu má poskytnúť odľahčené prekvapenie v podobe heretickej mozarti(r)ády Leck mich am Arsch, Jonicu! (2017). Ducha(m)plná enigma v názve odkazuje na Amadeovu nemiestnu slovnú hračku, ktorú Ďuriš vyumelkovane zaobalil do transžánrového soundu, v duchu kľúčovej tézy postmodernej estetiky „anything goes“.

Záhrada tretia

Silhouettes (2017) vracajú poslucháča do sveta zvukopriestorových fantómov, kde sú siluety možných entít náznakovo simulované hrou na päťstrunovom sláčikovom nástroji „Milanolo“, hybride huslí a violy; pre huslistu Milana Paľu ho vyrobili v brnianskej husliarskej dielni Bursík. Siluety sú spoločné dielo skladateľov Ďuriša a Rudolfa Pepuchu a virtuózneho inštrumentalistu Paľu. Živé Milanolo zakresľuje do syntetickým soundom modulovaného priestoru dynamické krivky, po ktorých zostávajú iba efemérne siluety, prezenčné stopy skutočnej prítomnosti ručne rozoznievaných siločiar v časopriestore s virtuálnymi súradnicami. Chronos I (1983), Ďurišova elektroakustická prvotina, je záhrada per excellence. Je to húževnatý sónický porast vo vegetačnom vývoji, kde je dominantný rytmický motív arborescentnej povahy naprieč prerastený rizómový refrénmi, ktoré, vzhľadom na priam autoreferenčnú reprezentáciu času, nie je v pulzujúcom poraste ľahké deteritorializovať. Hudba a jej primárne médium čas sú tu organicky „zrastené“, splývajú v posluchovej nemožnosti určiť hranicu medzi chronometrickým metrom a voľne pulzujúcim rytmom.

Záhrada štvrtá

Ephēmeros (2021) je ex-ante soundtrack k videu Jakuba Pišeka. Opäť je to úvodná melódia z prvej záhrady, ktorá otvára priestor, v tomto prípade artificiálnu mimočasovú krajinu. Melanchólia teda zostáva, fantómová dištancia však naberá (fantasmagorické) obrátky, zvukové i vizuálne. Zmätený poslucháč/divák sa ocitá na rozhraní dvoch svetov, violončelová melódia ho udržiava v tom zmyslovom, elektronická zvuková výprava ho teleprezentuje do nedohľadných končín kozmonautickej fikcie. Keby tak tušil, že sci-fi prostredie bolo simulované v kúpeľni, kde aluzívna „krútňava“ v bubne práčky sugeruje fabulácie za hranicami bežnej predstavivosti… Nemenej sugestívne Sny (1987) sú úplne vystavané na asociovaní priestorových vzťahov prostredníctvom stereometrického rozvíjania zvukových „plošín“. Striedavo i paralelne konštruované juxtapozície odznievaní a doznievaní abstraktných i „konkrétnych“ zvukov sú využité so zámerom evokovať snovú surrealitu. Bohatá, účelovo budovaná sonoristika raného diela prezrádza, akými smermi sa bude Ďurišova zvukotvorba uberať v nadchádzajúcich rokoch. Pretože záhrady nie sú usporiadané chronologicky, ale podľa hudobno-estetických kritérií, poslucháč sa opakovane ocitá nielen vo virtuálnych priestoroch, ale tiež v časových slučkách, k čomu prispieva aj pôsobivý violončelový motív „večného návratu“.